Taken from: http://hidingundercovrs.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/the-battle-of-epping-forest-by-genesis.html

Note this is not the work of The Genesis Archive but we feel it should be hosted on here so that it is easy to find.

I’ve been listening to the Genesis album Selling England by the Pound now for 40 years. One track that I have always had something of a soft spot for is “The Battle of Epping Forest”. Although there are objectively better and more musically satisfying tracks elsewhere on the album, “Battle” kept my attention as a teenager; and still does. I love the witty lyrics, the double entendres and the cartoon-like characters with Bash Street Kids-style names.

I grew up in East Anglia and often went down to London, so I knew roughly where Epping was on the map. To me, then, the song appeared rooted in the real world. It seemed to report on real events, real-time, unlike the myth-laden (but equally attractive) romance of “Dancing Out with the Moonlit Knight” or “Firth of Fifth” or the rustic whimsy of “I Know What I Like”. “Battle” was packed with words and colourful characters, with humour and menace – and it had a proper boy’s-own story; a bizarre one, but it sounded genuine.

I’m no Genesis expert, and there are others who will know more about this song than I, but I was curious about its origins. “Taken from a news story concerning two rival gangs fighting over East-End Protection rights,” it said, on the lyric sheet that came with the original vinyl pressing. So what was that all about, then?

“I keep cuttings that interest me,” Peter Gabriel told writer Janis Schacht years later. “‘Battle of Epping Forest’ was taken from a genuine news story in The Times. When I went back to find the story I’d misplaced it, so I fabricated the whole thing around the story of two gangs fighting over protection rights in London’s East End.”

In fact it was the hard-nosed crime journalist Clive Borrell who inspired this absurd tale of gangland altercations in the woods. Borrell had covered the police investigation into the Krays and Richardsons, two London gangs of brothers who’d terrorised parts of the capital in the Sixties. These days their stories are well enough documented elsewhere (try Wikipedia) but back in the day Borrell’s reports in The Times kept the broadsheet-reading public up to date with events, and eventually the arrests and imprisonment of both gangs at the end of the decade.

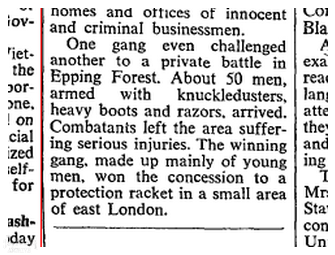

In the Krays’ wake came a jostling for supremacy of the next generation of gangsters. On 5 April 1972, The Times ran a front-page story, penned by Borrell, which reported on 40 raids by a Scotland Yard squad investigating gang crime in London. The raids followed a spate of violent crime across the city, mainly involving members of known gangs of criminals who for the previous two years had been trying to gain control of the underworld in east and south London – areas which had been gang free since the convictions of the Krays and Richardsons. Criminals, like nature, abhor a vacuum. Reported Borrell:

Unlike the Genesis song, however, there were no fatalities – or at least, none reported. The real-life Barking Slugs, Willie Wright, Mick the Prick, even poor old Harold Demure, all lived on to fight another day.

Reading the paper that Wednesday morning over his tea and toast, probably in his west London home, this sliver of reportage, just a few column inches on the front page, caught Gabriel’s eye. It was a good story, original; maybe the germ of a character-driven song there, something akin to “Harold the Barrel”. Peter snipped it out and filed it away somewhere safe. Over a year later, writing songs for what would become Selling England by the Pound, he had forgotten precisely where he’d put it.

In fact, probably unbeknownst to Gabriel, Epping Forest, out on the northeastern margins of the city where London dissolves into suburban Essex (somewhere I suspect the ex-Charterhouse pupil rarely – if at all – visited), had long been a scene of battle and conflict. The highwayman Dick Turpin knew this tract of woodland well and organised many criminal activities from a base between the Loughton Road and Kings Oak Road. In print, the original “Battle of Epping Forest” was fought by the Corporation of the City of London, to preserve the forest from enclosure as a sylvan playground for all Londoners, and the phrase appears as such in newspaper reports of the late nineteenth century.

Genesis

[Correction] Genesis had in fact played The Wake Arms (Pub), The Wake Arms roundabout on the outskirts of Epping Forest on the following dates: 23rd July 1972 and on the 5th November 1972.

December 1874

By the twentieth century, Epping Forest was more than just a place for recreation. The people were getting restless. The London Metropolitan Archives hold a letter amongst their Epping Forest files , summarised as a

Complaint of the noisy behaviour of a number of boys gathering on a piece of forest land in front of the writer’s house. Some tree trunks were deposited on the land, they sit on these. On Sundays gangs of youths gather ‘to do battle’. This is before it is light. They wander about yelling and singing… (no. 246, dated 1912 p.102)

Six decades later, Clive Borrell, again, describes the use of the forest as a rendezvous by the Krays and their associates in his book Crime in Britain Today (1975). These meetings were arranged “always at night and in the Epping Forest area, for suitcases of money to be dropped at pre-arranged spots.” Several such stories came out during or after the Krays’ trial. “One story they never recounted – and it is probably a significant insight into their characters,” writes Borrell, “was how they bought a string of ponies and used them to play Cowboys and Indians in Epping Forest.” It’s a detail that would have fitted well into Gabriel’s song.

Few adults in Britain at the time would have been unaware of the Krays’ arrest and conviction – the unpleasant details filled tabloid pages well into the Seventies and have since seeped into modern popular mythology. Whatever Gabriel knew of the background in 1973, he was determined to put the lost story he’d read a year earlier in The Times into song. He devised a cast of likely characters and set them to work, thumping, clouting and scurrying up trees. It must have been great fun to write. Gabriel even digressed at one point into a comedic “song within a song” about a randy vicar, which had little to do with the central narrative. No matter – in it went, kitchen sink and all.

The rest of the band were aghast. “Peter took the song and wrote the lyric and we recorded the track,” recalled Phil Collins in the interviews conducted for the 2007 reissue of Selling England. “It’s like, 300 words per line. There was no space. All the air had been sucked out of it.” But there was no time, or no inclination, to trim the lyrics. Studio time was expensive and this was Island Studios, which I imagine did not come cheap. “If we had known we could have thinned it out. In those days we didn’t go back and rerecord things.” Played live it was, as Phil puts it, “a barrage of information being thrown at you.” In fact there were at least five studio takes of the song and the instrumental track to which Gabriel added his lyrics has since been leaked on bootlegs.

Peter concurs: “I spent a lot of time building up the characters. I was quite reluctant to edit as severely as I should have done. It did end up too wordy.” But an insight into the writing process for the song comes from Jerry Gilbert, who interviewed Gabriel for Sounds in August 1973, just as the band were putting finishing touches to Selling England. Gilbert is treated to a performance of the track:

Peter contemplates how he is going to end a new number, “The Battle of Epping Forest”, and then performs the song live in his own living room over a studio backing track, pausing for breath to throw in words of explanation during the instrumental links. Like some great novelist, Peter ponders on the ending once he has killed off the two rival gangs. A little couplet deciding the issue over the toss of a coin would tie up the song nicely but perhaps that’s too much of an anti-climax, he decides.(Sounds 1/9/73)

Of course Gabriel kept the ending and the Blackcap Barons flick a coin to finish the song. It was, indeed, an anti-climactic termination to the day’s scuffle: a no-score draw. So who were the Blackcap Barons? InEpping Forest Through the Ages, Georgina Green writes that

after the Civil War [i.e. 1651] the Forest gave sanctuary to a number of discharged soldiers turned outlaws, particularly a gang called the Waltham Blacks who blackened their faces when out robbing travellers or poaching the king’s deer.Ok, perhaps it is unlikely (especially since Green’s book was published in 1982), but could Gabriel have known this?

No, you ain’t seen nothing like it

Not since the Civil War…

Taken From:

http://hidingundercovrs.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/the-battle-of-epping-forest-by-genesis.html